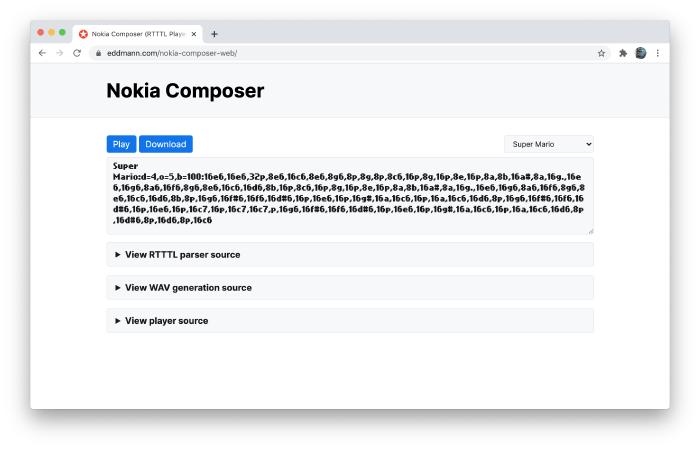

Building a Nokia Composer (RTTTL) Player and WAV-file Generator in the Browser

Who remembers punching in key-combinations found online into their Nokia 3210 to create custom ringtones? I spent more time than I would care to admit doing this in my youth. Over the weekend I decided, as a bit of a nostalgic exercise, to see if I could implement a Nokia Composer clone using JavaScript and the Web Audio API. From here, I expanded on the player to provide the ability to download the generated ringtone as a WAV file.

The finished player and WAV-file generator is available to experiment with and code-review on GitHub.

I decided to leverage in-line React and Babel so as to keep all the logic on a single webpage. This makes for a more succinct demo and provides the ability to automatically highlight the required code in-line.

Parsing RTTTL

A-Team:d=8,o=5,b=125:4d#6,a#,2d#6,16p,g#,4a#,4d#.,p,16g,16a#,d#6,a#,f6,2d#6,16p,c#.6,16c6,16a#,g#.,2a#

The above may look familiar to anyone who owned a Nokia in the early 2000s. This is an example of the Ring Tone Transfer Language (RTTTL) which was developed by Nokia to represent ringtones on their mobile devices. Using the provided specification (in Backus–Naur form), we can see that the input can be broken up into three distinct parts:

- Name – the name of the melody, which consists of a maximum of 10 characters.

- Defaults – the octave, duration and beat to default to if one is not specified in the given melody note (duration=4, octave=6, beat=63).

- Melody – a comma-separated listing of the notes, including optional duration, octave and special-duration dot.

I used this specification to begin parsing the input using JavaScript. Parsing the name attribute was omitted as this was not required to complete the scoped demonstration.

const toDefaults = unparsedDefaults =>

unparsedDefaults.split(",").reduce(

(defaults, option) => {

const [key, value] = option.split("=");

switch (key) {

case "d":

return { ...defaults, duration: value };

case "o":

return { ...defaults, octave: value };

case "b":

return { ...defaults, beat: value };

default:

return defaults;

}

},

{ duration: 4, octave: 6, beat: 63 }

);

const toMelody = (melody, defaults) => {

// ..

return melody.split(",").map(unparsedNote => {

const { groups: parsed } = unparsedNote.match(

/(?<duration>1|2|4|8|16|32|64)?(?<note>(?:[a-g]|p)#?){1}(?<dot>\.?)(?<octave>4|5|6|7)?/

);

const { duration, note, dot, octave, beat } = Object.keys(parsed).reduce(

(xs, x) => (parsed[x] ? { ...xs, [x]: parsed[x] } : xs),

defaults

);

// ..

});

};

const parse = rtttl => {

const [_, unparsedDefaults, unparsedMelody] = rtttl.split(":", 3);

return toMelody(unparsedMelody, toDefaults(unparsedDefaults));

};

Looking at the above code, you can see the described sections are broken apart, with the default values and melody notes subsequently being parsed individually. The default values are parsed first so as to have these available when parsing the melody section. Using the supplied specification, I was able to ensure that only valid melody notes were parsed. I found that using regular expression named capture groups provided a very elegant means to produce the defined values per note (providing defaults were used where there were omissions).

A Tiny Bit of Music Theory

With the RTTTL now parsed, my next objective was to translate the defined note/octaves of the melody into frequencies which I could send to the Oscillator.

This led me to research the Twelve-Tone Equal Temperament system of tuning.

Using this system and a little bit of maths, we are able to calculate the frequency of a given note/octave using a known base note frequency.

Typically, A4 (also known as Stuttgart pitch, 440Hz) is used as the base frequency from which all calculations are done; however, I noticed that if I instead use C4 (Middle-C, 261.63Hz), it would save some offset maths calculations from being required.

The formula below provides the ability to calculate the octave frequency of a given note.

This formula can be used to calculate the octave one lower and one higher than the provided frequency (in this case C4) as shown in JavaScript:

const C4 = 261.63;

const C3 = C4 * 2 ** (3 - 4); // 130.81

const C5 = C4 * 2 ** (5 - 4); // 523.26

Furthermore, the formula below provides the ability to calculate the frequency of a desired note.

This uses the offset from the base note within the scale (c, c#, d, d#, e, f, f#, g, g#, a, a#, b) to determine the frequency.

This formula can again be implemented in JavaScript to calculate the note one lower and one higher than the provided frequency (in this case C4).

Notice that using C as the base note allows the omission of any offset calculation needing to be applied, thanks to the array being zero-indexed.

const NOTES = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const C4 = 261.63;

const B4 = C4 * 2 ** (NOTES.indexOf("b") / 12); // 493.89

const D4 = C4 * 2 ** (NOTES.indexOf("d") / 12); // 293.69

Finally, the two formulas can be combined to calculate the desired note/octave from a given reference point.

This formula can then be used to generate the frequencies for all notes/octaves, producing a scale. Providing any valid base frequency will, in turn, produce the same exact scale representation.

const NOTES = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const scales = (baseNote, baseOctave, baseFrequency) =>

NOTES.reduce(

(scale, note) =>

[...Array(9).keys()].reduce(

(scale, octave) => ({

...scale,

[note + octave]:

baseFrequency *

2 **

(octave -

baseOctave +

(NOTES.indexOf(note) - NOTES.indexOf(baseNote)) / NOTES.length),

}),

scale

),

{}

);

scales("c", 4, 261.63);

scales("a", 4, 440);

scales("a", 0, 27.5);

I used this exploration exercise as the basis to complete parsing the RTTTL input into a playable form.

const toMelody = (melody, defaults) => {

const notes = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const middleC = 261.63;

return melody.split(",").map(unparsedNote => {

const { groups: parsed } = unparsedNote.match(

/(?<duration>1|2|4|8|16|32|64)?(?<note>(?:[a-g]|p)#?){1}(?<dot>\.?)(?<octave>4|5|6|7)?/

);

const { duration, note, dot, octave, beat } = Object.keys(parsed).reduce(

(xs, x) => (parsed[x] ? { ...xs, [x]: parsed[x] } : xs),

defaults

);

return {

duration: (240 / beat / duration) * (dot ? 1.5 : 1),

frequency:

note === "p" ? 0 : middleC * 2 ** (octave - 4 + notes.indexOf(note) / 12),

};

});

};

With this in place, the parse function now returns an ordered listing of all the note durations and frequencies based on the supplied RTTTL.

Getting it to Play

From here, I then created a simple React component which provided the ability to supply a given RTTTL composition and play it.

function NokiaComposer({ melodies }) {

const [isPlaying, setPlaying] = React.useState(false);

const [composition, setComposition] = React.useState(melodies[0] || "");

React.useEffect(() => {

if (!isPlaying) return;

const audio = new AudioContext();

const oscillator = audio.createOscillator();

oscillator.type = "square";

oscillator.connect(audio.destination);

oscillator.onended = () => setPlaying(false);

let time = 0;

oscillator.start();

parse(composition).forEach(({ duration, frequency }) => {

oscillator.frequency.setValueAtTime(frequency, time);

time += duration;

});

oscillator.stop(time);

return async () => {

await audio.close();

};

}, [isPlaying]);

// ...

}

Using the parsed RTTTL and the Web Audio API’s AudioContext/Oscillator, I am able to cycle through the melody, ensuring that the given frequency is set for the desired duration within the Oscillator.

This completed the implementation required to play the composition within the browser 🎉.

Generating WAV files

The final step to this demonstration was adding the ability to generate a WAV file from the supplied RTTTL composition.

Thanks to the OfflineAudioContext, I was able to employ the same logic described above to generate an in-memory AudioBuffer representation of the melody.

const generateAudioBuffer = async rtttl => {

const melody = parse(rtttl);

const totalDuration = melody.reduce((total, { duration }) => total + duration, 0);

const audio = new OfflineAudioContext(1, totalDuration * 44100, 44100);

const oscillator = audio.createOscillator();

oscillator.type = "square";

oscillator.connect(audio.destination);

let time = 0;

oscillator.start();

melody.forEach(({ duration, frequency }) => {

oscillator.frequency.setValueAtTime(frequency, time);

time += duration;

});

oscillator.stop(time);

return audio.startRendering();

};

From here, I spent a little time researching into how a WAV file was formed, electing to create a 32-bit floating-point WAV file representation of the melody.

const generateWavBlob = audioBuffer => {

const writeString = (view, offset, string) => {

string.split("").forEach((character, index) => {

view.setUint8(offset + index, character.charCodeAt());

});

};

const samples = audioBuffer.getChannelData(0);

const bytesPerSample = 4;

const buffer = new ArrayBuffer(44 + samples.length * bytesPerSample);

const view = new DataView(buffer);

writeString(view, 0, "RIFF"); // ChunkID

view.setUint32(4, 36 + samples.length * bytesPerSample, true); // ChunkSize

writeString(view, 8, "WAVE"); // Format

writeString(view, 12, "fmt "); // Subchunk1ID

view.setUint32(16, 16, true); // Subchunk1Size

view.setUint16(20, 3, true); // AudioFormat (IEEE float)

view.setUint16(22, 1, true); // NumChannels

view.setUint32(24, audioBuffer.sampleRate, true); // SampleRate

view.setUint32(28, audioBuffer.sampleRate * bytesPerSample, true); // ByteRate

view.setUint16(32, bytesPerSample, true); // BlockAlign

view.setUint16(34, 32, true); // BitsPerSample

writeString(view, 36, "data"); // Subchunk2ID

view.setUint32(40, samples.length * bytesPerSample, true); // Subchunk2Size

samples.forEach((sample, index) => {

view.setFloat32(44 + index * bytesPerSample, sample, true); // Data

});

return new Blob([view], { type: "audio/wav" });

};

Finally, I added the ability to automatically download the generated WAV blob as a named file within the browser.

function NokiaComposer({ melodies }) {

// ...

const handleDownload = async e => {

const blob = generateWavBlob(await generateAudioBuffer(composition));

const autoDownloadLink = document.createElement("a");

autoDownloadLink.href = window.URL.createObjectURL(blob);

autoDownloadLink.download = composition.split(":")[0];

autoDownloadLink.click();

};

// ..

}

Conclusion

To conclude, I enjoyed exploring how Nokia ringtones were represented in RTTTL, and how you could use a little bit of music theory and maths to generate the corresponding frequencies.

The Web Audio API’s AudioContext/Oscillator abstracted away many of the intricacies required to produce the desired sounds.

This allowed me to play the sound in real-time as well as produce an in-memory representation from which I could generate a WAV file.

I found the most interesting part of the exercise was researching how a WAV file is constructed at a raw bits/bytes level.