Building a Nokia Composer (RTTTL) Player and WAV-file Generator in the Browser

Who remembers punching in key-combinations found online into their Nokia 3210 to create custom ringtones? I spent more time than I would to admit doing this in my youth. Over the weekend I decided as a bit of an nostalgic exercise to see if I could implement a Nokia Composer clone using JavaScript and the Web Audio API. From here, I expanded on the player to provide the ability to download the generated ringtone as a WAV file.

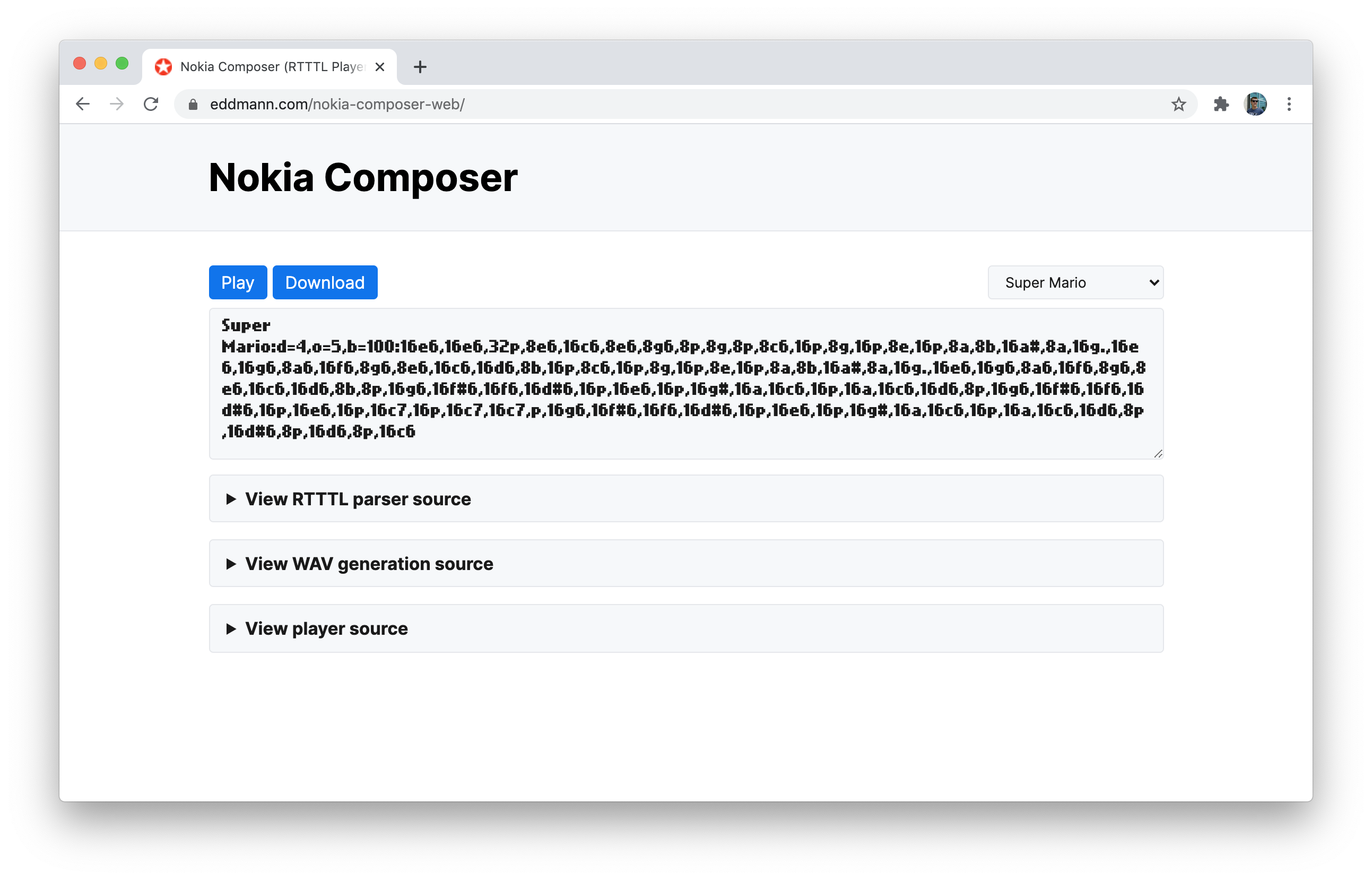

The finished player and WAV-file generator is available to experiment with and code-review on GitHub.

I decided to leverage in-line React and Babel, so as to keep all the logic on a single webpage. This makes for a more succient demo, and provides the ability to automatically highlight the required code in-line.

Parsing RTTTL

A-Team:d=8,o=5,b=125:4d#6,a#,2d#6,16p,g#,4a#,4d#.,p,16g,16a#,d#6,a#,f6,2d#6,16p,c#.6,16c6,16a#,g#.,2a#

The above may look familiar to anyone who owned a Nokia in the early 2000’s. This is an example of the Ring Tone Transfer Language (RTTTL) which was developed by Nokia to represent ringtones on their mobile devices. Using the provided specification (in Backus–Naur form), we can see that the input can be broken up into three distinct parts:

- Name - the name of the melody, which consits of a maxium of 10 characters.

- Defaults - The octave, duration and beat to default to if one is not specified in the given melody note (duration=4, octave=6, beat=63).

- Melody - Comma-seperated listing of the notes - including optional duration, octave and special-duration dot.

I used this specification to begin parsing the input using JavaScript. Parsing the name attribute was omitted as this was not required to complete the scoped demostration.

const toDefaults = unparsedDefaults =>

unparsedDefaults.split(",").reduce(

(defaults, option) => {

const [key, value] = option.split("=");

switch (key) {

case "d":

return { ...defaults, duration: value };

case "o":

return { ...defaults, octave: value };

case "b":

return { ...defaults, beat: value };

default:

return defaults;

}

},

{ duration: 4, octave: 6, beat: 63 }

);

const toMelody = (melody, defaults) => {

// ..

return melody.split(",").map(unparsedNote => {

const { groups: parsed } = unparsedNote.match(

/(?<duration>1|2|4|8|16|32|64)?(?<note>(?:[a-g]|p)#?){1}(?<dot>\.?)(?<octave>4|5|6|7)?/

);

const { duration, note, dot, octave, beat } = Object.keys(parsed).reduce(

(xs, x) => (parsed[x] ? { ...xs, [x]: parsed[x] } : xs),

defaults

);

// ..

});

};

const parse = rtttl => {

const [_, unparsedDefaults, unparsedMelody] = rtttl.split(":", 3);

return toMelody(unparsedMelody, toDefaults(unparsedDefaults));

};

Looking at the above code you can see the described sections are broken apart, with the default values and melody notes subsquently being parsed individually. The default values are parsed first, so as to have these available when parsing the melody section. Using the supplied specification I was able to ensure that only valid melody notes were parsed. I found using regular expression named capture groups provided a very elegant means to produce the defined values per note (providing defaults were there were omissions).

A Tiny Bit of Music Theory

With the RTTTL now parsed, my next objective was to translate the defined note/octaves of the melody into frequencies of which I could send to the Oscillator.

This lead me to research into the the Twelve-Tone Equal Temperament system of tuning.

Using this system and alittle bit of Math, we are able to calculate the frequency of a given note/octave using a known base note frequency.

Typically A4 (aka Stuttgart pitch, 440Hz) is used as the base frequency of which all calculations are done, however, I noticed that if I instead use C4 (Middle-C, 261.63Hz) it would save some offset Math calculations being required.

The formula below provides the ability to calculate the octave frequency of a given note.

This formula can be used to calculate the octave one lower and one higher than the provided frequency (in this case C4) like so in JavaScript:

const C4 = 261.63;

const C3 = C4 * 2 ** (3 - 4); // 130.81

const C5 = C4 * 2 ** (5 - 4); // 523.26

Further more, the formula below provides the ability to calculate the frequency of a desired note.

This uses the offset from the base note within the scale (c, c#, d, d#, e, f, f#, g, g#, a, a#, b) to determine the frequency.

This forumla can again be implemented in JavaScript to calculate the note one lower and one higher than the provided frequency (in this case C4):

Notice that using C as the base note allows omission of any offset calculation needing to be applied, thanks to the the array being zero-indexed.

const NOTES = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const C4 = 261.63;

const B4 = C4 * 2 ** (NOTES.indexOf("b") / 12); // 493.89

const D4 = C4 * 2 ** (NOTES.indexOf("d") / 12); // 293.69

Finally, the two formulas can be combined to calculate the desired note/octave from a given reference point.

This formula can then be used to generate the frequencies for all notes/octaves, producing a scale. Providing any valid base frequency will in-turn produce the same exact scale representation.

const NOTES = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const scales = (baseNote, baseOctave, baseFrequency) =>

NOTES.reduce(

(scale, note) =>

[...Array(9).keys()].reduce(

(scale, octave) => ({

...scale,

[note + octave]:

baseFrequency *

2 **

(octave -

baseOctave +

(NOTES.indexOf(note) - NOTES.indexOf(baseNote)) / NOTES.length),

}),

scale

),

{}

);

scales("c", 4, 261.63);

scales("a", 4, 440);

scales("a", 0, 27.5);

I used this exploration exercise as the bases to complete parsing the RTTTL input into a playable form.

const toMelody = (melody, defaults) => {

const notes = ["c", "c#", "d", "d#", "e", "f", "f#", "g", "g#", "a", "a#", "b"];

const middleC = 261.63;

return melody.split(",").map(unparsedNote => {

const { groups: parsed } = unparsedNote.match(

/(?<duration>1|2|4|8|16|32|64)?(?<note>(?:[a-g]|p)#?){1}(?<dot>\.?)(?<octave>4|5|6|7)?/

);

const { duration, note, dot, octave, beat } = Object.keys(parsed).reduce(

(xs, x) => (parsed[x] ? { ...xs, [x]: parsed[x] } : xs),

defaults

);

return {

duration: (240 / beat / duration) * (dot ? 1.5 : 1),

frequency:

note === "p" ? 0 : middleC * 2 ** (octave - 4 + notes.indexOf(note) / 12),

};

});

};

With this in-place, the parse function now returns an ordered listing of all the note durations and frequencies based on the supplied RTTTL.

Getting it to Play

From here, I then created a simple React component which provided the ability to supply a given RTTTL composition and play it.

function NokiaComposer({ melodies }) {

const [isPlaying, setPlaying] = React.useState(false);

const [composition, setComposition] = React.useState(melodies[0] || "");

React.useEffect(() => {

if (!isPlaying) return;

const audio = new AudioContext();

const oscillator = audio.createOscillator();

oscillator.type = "square";

oscillator.connect(audio.destination);

oscillator.onended = () => setPlaying(false);

let time = 0;

oscillator.start();

parse(composition).forEach(({ duration, frequency }) => {

oscillator.frequency.setValueAtTime(frequency, time);

time += duration;

});

oscillator.stop(time);

return async () => {

await audio.close();

};

}, [isPlaying]);

// ...

}

Using the parsed RTTTL and Web Audio API AudioContext/Oscillator, I am able to cycle through the melody ensuring that the given frequency is set for the desired duration within the Oscillator.

This completed the implementation required to play the composition within the Browser 🎉.

Generating WAV files

The final step to this demostration was adding the ability to generate a WAV file from the supplied RTTTL composition.

Thanks to the OfflineAudioContext, I was able to employ the same logic described above to generate an in-memory AudioBuffer representation of the melody.

const generateAudioBuffer = async rtttl => {

const melody = parse(rtttl);

const totalDuration = melody.reduce((total, { duration }) => total + duration, 0);

const audio = new OfflineAudioContext(1, totalDuration * 44100, 44100);

const oscillator = audio.createOscillator();

oscillator.type = "square";

oscillator.connect(audio.destination);

let time = 0;

oscillator.start();

melody.forEach(({ duration, frequency }) => {

oscillator.frequency.setValueAtTime(frequency, time);

time += duration;

});

oscillator.stop(time);

return audio.startRendering();

};

From here, I spent alittle time researching into how a WAV file was formed, electing to create a 32-bit float-point WAV file representation of the melody.

const generateWavBlob = audioBuffer => {

const writeString = (view, offset, string) => {

string.split("").forEach((character, index) => {

view.setUint8(offset + index, character.charCodeAt());

});

};

const samples = audioBuffer.getChannelData(0);

const bytesPerSample = 4;

const buffer = new ArrayBuffer(44 + samples.length * bytesPerSample);

const view = new DataView(buffer);

writeString(view, 0, "RIFF"); // ChunkID

view.setUint32(4, 36 + samples.length * bytesPerSample, true); // ChunkSize

writeString(view, 8, "WAVE"); // Format

writeString(view, 12, "fmt "); // Subchunk1ID

view.setUint32(16, 16, true); // Subchunk1Size

view.setUint16(20, 3, true); // AudioFormat (IEEE float)

view.setUint16(22, 1, true); // NumChannels

view.setUint32(24, audioBuffer.sampleRate, true); // SampleRate

view.setUint32(28, audioBuffer.sampleRate * bytesPerSample, true); // ByteRate

view.setUint16(32, bytesPerSample, true); // BlockAlign

view.setUint16(34, 32, true); // BitsPerSample

writeString(view, 36, "data"); // Subchunk2ID

view.setUint32(40, samples.length * bytesPerSample, true); // Subchunk2Size

samples.forEach((sample, index) => {

view.setFloat32(44 + index * bytesPerSample, sample, true); // Data

});

return new Blob([view], { type: "audio/wav" });

};

Finally, I added the ability to automatically download the generated WAV blob as a named file within the Browser.

function NokiaComposer({ melodies }) {

// ...

const handleDownload = async e => {

const blob = generateWavBlob(await generateAudioBuffer(composition));

const autoDownloadLink = document.createElement("a");

autoDownloadLink.href = window.URL.createObjectURL(blob);

autoDownloadLink.download = composition.split(":")[0];

autoDownloadLink.click();

};

// ..

}

Conclusion

To conclude, I enjoyed exploring how Nokia ringtones were represented in RTTTL, and how you could use alittle bit of Music Theory/Math to generate the corresponding frequencies.

The Web Audio API AudioContext/Oscillator abstracted away alot of intricacies required to produce the desired sounds.

This allowed me to play the sound in real-time, as well was produce an in-memory representation that I could generate a WAV file from.

I found the most interesting part of the exercise was researching into how a WAV files was constructed, from a raw bits/bytes level.