Building an Enigma Machine in Haskell

Following on from my previous post which highlighted my experience building an Enigma Machine in ClojureScript, I decided it would be interesting to model the machine within Haskell. I felt solving the same problem in this mannor would be a great way to compare and contrast Lisp and heavily-typed languages such as Haskell. Through this process I also wanted to explore using Hspec and QuickCheck for comparable Property-based testing that I achieved in the ClojureScript counterpart.

You can experiment with the final implementation by pulling down the GitHub repository and using the provided Makefile encode Makefile target.

We leverage Docker to containerise the Haskell development/testing requirements when being run locally and during CI.

How it works

I spent some time within the previous ClojureScript implementation discussing the purpose and inner-workings of the Enigma Machine. So as to not simply repeat myself here I ask that you refer to this section for a basic understanding of the machine behaviour we will be modeling.

The Machine

In a similar fashion to how we tackled the previous implementation, the first element of the machine that we will model are the Rotors.

alphabet :: [Char]

alphabet = ['A'..'Z']

data Rotor = Rotor { _out :: String, _in :: String, _step :: Char }

deriving (Show)

type Rotors = (Rotor, Rotor, Rotor)

rotorI :: Rotor

rotorI = Rotor "EKMFLGDQVZNTOWYHXUSPAIBRCJ" alphabet 'Q'

rotorII :: Rotor

rotorII = Rotor "AJDKSIRUXBLHWTMCQGZNPYFVOE" alphabet 'E'

rotorIII :: Rotor

rotorIII = Rotor "BDFHJLCPRTXVZNYEIWGAKMUSQO" alphabet 'V'

isStep :: Rotor -> Bool

isStep rotor = _step rotor == head (_in rotor)

rotate :: Rotor -> Rotor

rotate (Rotor _out _in _step) = Rotor (tail _out ++ [head _out]) (tail _in ++ [head _in]) _step

rotateAll :: Rotors -> Rotors

rotateAll (a, b, c) = (rotate a, if isStep a || isStep b then rotate b else b, if isStep b then rotate c else c)

passthrough :: Rotor -> Char -> Char

passthrough rotor letter = maybe '?' id (lookup letter in' >>= (flip lookup) out')

where in' = zip alphabet (_out rotor)

out' = zip (_in rotor) alphabet

passthroughAll :: Rotors -> Char -> Char

passthroughAll (a, b, c) letter = passthrough c . passthrough b . passthrough a $ letter

invert :: Rotor -> Rotor

invert (Rotor _out _in _step) = Rotor _in _out _step

invertedPassthroughAll :: Rotors -> Char -> Char

invertedPassthroughAll (a, b, c) letter = passthrough (invert a) . passthrough (invert b) . passthrough (invert c) $ letter

Based on the code above we first create a new data type which will represent a given Rotor - along with an aggregate tuple which represents the collection of Rotors. This leads us to providing the behaviour necessary to rotate the Rotor collection based on each given Rotors position and step. Finally, we provide a means of passing a given letter through (and back-through) the Rotors, performing the substitution encryption (scrambled wiring) along the way.

From here, we will now model the Reflector, which is used to complete the circuit and send the current (letter) back through the Rotors.

type Reflector = [(Char, Char)]

reflectorA :: Reflector

reflectorA = zip alphabet "EJMZALYXVBWFCRQUONTSPIKHGD"

reflectorB :: Reflector

reflectorB = zip alphabet "YRUHQSLDPXNGOKMIEBFZCWVJAT"

reflectorC :: Reflector

reflectorC = zip alphabet "FVPJIAOYEDRZXWGCTKUQSBNMHL"

reflect :: Reflector -> Char -> Char

reflect reflector letter = maybe '?' id $ lookup letter reflector

Being a static substitution system the Reflector is trival to model - however, we do cater for the possibility of a value not being present in the ‘lookup’ invocation via unwrapping the Maybe and returning an ? instead.

This should not occur in practise, but to date I have not been able to find a means of adding the sufficent type-level constraints required to ensure that only Char values present in the alphabet listing should be consumed/returned.

This leads us on to modeling the Plugboard, which uses the lookup Haskell function again to see if a translation (plug) for the given letter has been provided.

If this is not the case when unwrapping the Maybe monadic structure, the provided letter itself (by-way of the id function) is returned instead.

type Plugboard = [(Char, Char)]

plug :: Plugboard -> Char -> Char

plug plugboard letter = maybe letter id $ lookup letter plugboard'

where plugboard' = (plugboard ++ map swap plugboard)

With all the building blocks now in-place we can begin to compose them together to handle encoding a given message through the machine.

encode :: Rotors -> Reflector -> Plugboard -> Char -> Char

encode rotors reflector plugboard letter =

plug plugboard . invertedPassthroughAll rotors . reflect reflector . passthroughAll rotors . plug plugboard $ letter

encodeMessage :: Rotors -> Reflector -> Plugboard -> String -> String

encodeMessage _ _ _ "" = ""

encodeMessage rotors reflector plugboard (letter : letters) =

let rotated = rotateAll rotors in

encode rotated reflector plugboard letter : encodeMessage rotated reflector plugboard letters

Above we have opted to break the problem up into a recursive encodeMessage function which uses an internal encode function to provide threading the letter through the currently configured machine.

Unlike Clojure we do not have a means to express ‘threading’ the letter through a list of functions defined left-to-right.

Instead we have to compose the functions together reading the function right-to-left.

It would be nice to be able to provide some syntactic sugar around this use-case - as when you have big composition chains such as this, it is a lot more understable to read left-to-right (regardless of how the call stack is going to be built internally).

Testing

With the machine behaviour now modeled in code we can move on to asserting its correctness. In a similar fashion to how we tested the ClojureScript implementation, I have opted to explore testing using static example-based test-cases, along with random examples which ensure desired properties of the machine hold true.

genReflector :: Gen Reflector

genReflector = elements [reflectorA, reflectorB, reflectorB]

genRotor :: Gen Rotor

genRotor = elements [rotorI, rotorII, rotorIII]

genRotors :: Gen Rotors

genRotors = liftM3 (,,) genRotor genRotor genRotor

plugboard :: [Char] -> [(Char, Char)]

plugboard zs = zip xs ys

where (xs, ys) = splitAt ((length zs + 1) `div` 2) zs

genPlugboard :: Gen Plugboard

genPlugboard = fmap plugboard $ shuffle alphabet

genMessage :: Gen String

genMessage = listOf $ elements alphabet

Using QuickCheck, we are able to succinctly provide a means of defining how a valid machine configuration and message input should be constructed. One omission to this implementation that should be highlighted is that we do not provide the operator with the ability to specify the Rotor starting positions. This can be trivially added but I decided that in the interest of code-sample clarity I would leave this as an exercise of the reader to implement if they so wish.

main :: IO ()

main = hspec $ do

describe "Machine" $ do

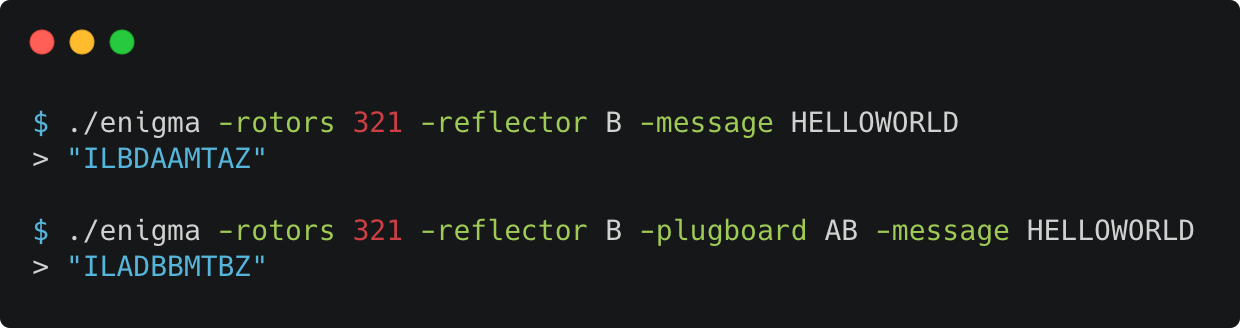

it "encodes message without plugboard" $ do

encodeMessage (rotorIII, rotorII, rotorI) reflectorB [] "HELLOWORLD" `shouldBe` "ILBDAAMTAZ"

it "encodes message with plugboard" $ do

encodeMessage (rotorIII, rotorII, rotorI) reflectorB [('A', 'B')] "HELLOWORLD" `shouldBe` "ILADBBMTBZ"

it "encoded cipher matches message" $ do

property $ forAll genReflector $ \reflector ->

forAll genRotors $ \rotors ->

forAll genPlugboard $ \plugboard ->

forAll genMessage $ \message ->

let cipher = encodeMessage rotors reflector plugboard message in

message == encodeMessage rotors reflector plugboard cipher

it "cipher is same length as message" $ do

property $ forAll genReflector $ \reflector ->

forAll genRotors $ \rotors ->

forAll genPlugboard $ \plugboard ->

forAll genMessage $ \message ->

let cipher = encodeMessage rotors reflector plugboard message in

length message == length cipher

Coupled with the help of Hspec we are then able to define the two static example-based tests that we created before, along with the two machine properties that we wish to hold true. Although the syntax is naturally different, the general philosophy of how a Property-based test is expressed and validated is very similar to the ClojureScript counterpart.

As stated in the previous article this test-suite is by no means exhaustive and can be expanded upon greatly.

The goal of this is to highlight the key differences between conventional test assertions and testing validity of System under test (SUT) properties.

This test-suite can be run locally using the make test target, or you can see example resulting output by-way of the configured GitHub Action.

The User Interface

To make this implementation a little different I have opted to provide a Command-line based user interface over a Web-based one. In doing so we are able to see a very powerful use-case for Haskell’s pattern matching functionality.

To achieve this end-goal we must first provide a means for the client to translate their desired machine configuration into one that our encodeMessage function can understand.

toRotor :: Char -> Maybe Rotor

toRotor = (flip lookup) [('1', rotorI), ('2', rotorII), ('3', rotorIII)]

toReflector :: Char -> Maybe Reflector

toReflector = (flip lookup) [('A', reflectorA), ('B', reflectorB), ('C', reflectorC)]

toPlugboard :: String -> Plugboard

toPlugboard (x : y : xs) = [(toUpper x, toUpper y)] ++ toPlugboard xs

toPlugboard _ = []

With this functionality now in-place we can move on to parsing the Command-line argument input. Thanks to how powerful Haskell’s pattern matching is, we are able to concisely break-up the problem of parsing each of the required machine components as follows.

parseRotors :: [String] -> IO Rotors

parseRotors ("-rotors" : [a, b, c] : _) = case (toRotor a, toRotor b, toRotor c) of

(Just a', Just b', Just c') -> pure (a', b', c')

_ -> fail $ "invalid rotors " ++ [a, b, c] ++ " specified in args"

parseRotors (_ : xs) = parseRotors xs

parseRotors [] = fail "rotors must be specified in args"

parsePlugboard :: [String] -> IO Plugboard

parsePlugboard ("-plugboard" : plugboard : _) = pure $ toPlugboard plugboard

parsePlugboard (_ : xs) = parsePlugboard xs

parsePlugboard [] = pure []

parseReflector :: [String] -> IO Reflector

parseReflector ("-reflector" : [reflector] : _) = case (toReflector . toUpper) reflector of

Just reflector' -> pure reflector'

Nothing -> fail $ "invalid reflector " ++ [reflector] ++ " specified in args"

parseReflector (_ : xs) = parseReflector xs

parseReflector [] = fail "reflector must be specified in args"

parseMessage :: [String] -> IO String

parseMessage ("-message" : message : _) = pure $ map toUpper message

parseMessage (_ : xs) = parseMessage xs

parseMessage [] = fail "message must be specified in args"

I have decided to take advantage of the IO Monad and return a wrapped value for each given parsed configuration option. This allows us to neatly use do notation described below to build a fully configured machine, short circuiting at any stage where we are unable to parse the given input option.

main :: IO ()

main = do

args <- System.Environment.getArgs

rotors <- parseRotors args

reflector <- parseReflector args

plugboard <- parsePlugboard args

message <- parseMessage args

print $ encodeMessage rotors reflector plugboard message

With the machine configuration successfully parsed we are able to invoke the encodeMessage function and print the resulting cipher message to the Terminal.

Conclusion

I felt reimplementing the Enigma Machine in Haskell was a very worthwhile endeavour, allowing me to compare and contrast how the problem can be solved in the two different languages. I am big fan of Lisp and the Clojure dialect, but did find how useful declaring functions by means of simple type transformations was a very pleasing/powerful development process. Starting off by thinking in soley type transformations as opposed to concrete behaviour provided a means to build up the system in a very succinct manner. From here, I hope to spend some additional time solving future problems using Haskell, taking more time to leverage further aspects of its very expressive type system.