Mince Pie Challenge: Adding Test Coverage using Jest and Travis CI

Following on from adding Flow to the API project, I now wish to garner further confidence in the code by adding tests. In this post I will document the process of setting up the test-runner Jest, and adding suitable test coverage to the current authentication example.

If you are keen to see how the finished example looks, you can access it within the API repository.

Developed by Facebook, Jest is a unit testing framework that prides itself on minimal setup and configuration overhead.

This claim is aided by the assertion library, rich mocking support and snapshot testing provided out-of-the-box.

Following several standard conventions, such as placing tests within a __tests__ directory, Jest is able to automatically locate tests and run them in parallel for speed.

One source of confusion when looking at Jest is the misrepresentation that it can only target React-based applications. This is not the case, and is highlighted as such in their own documentation.

Although Jest may be considered a React-specific test runner, in fact it is a universal testing platform, with the ability to adapt to any JavaScript library or framework. You can use Jest to test any JavaScript code.

This is great, as it means we can take advantage of the awesome features discussed, regardless of the JavaScript application we are building.

Setting up Jest

Now we have familiarised ourselves with what Jest can do, let us begin by getting it set up within the project.

The first step is to add the following configuration to the package.json file.

{

"devDependencies": {

"jest": "^23.1.0"

},

"scripts": {

"test": "jest"

},

"jest": {

"rootDir": "./src",

"cacheDirectory": "./node_modules/.cache/jest"

}

}

Along with the expected development dependency, we add the new script definition which will allow us to execute the test suite by simply running npm test.

Finally, we configure several Jest-specific options, the first of which is to specify the root location to search for tests.

We also configure where Jest should store any cached items (to speed up test execution), opting for within node_modules as the Docker setup stores this within a stateful volume.

We can now add a new target to the Makefile to easily invoke desired test invocations.

test:

docker-compose run --rm serverless npm test

As we are using Jest in an application that does not include external assets (such as images or stylesheets), we do not need to worry about further configuring Webpack in this use case.

Separating the Domain Logic from the Delivery Mechanism

In the previous article we delved into adding types to the user authentication handler abstraction.

We will now expand upon this and provide sufficient test coverage to each of the three handler options.

To do this we must first break out each handler type into separate modules, where we will define the handler up to the point that we require the concrete services.

We will leave this responsibility to the specific delivery mechanism, in this instance that will be specified in src/auth.js.

First, we shall create a new file src/handlers/public.js, which will contain the ‘public’ handler definition.

// @flow

import { createHandler } from '../helpers/handlers';

const handler = async () => ({

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify({ userId: 'N/A' }),

});

export default createHandler(handler);

This handler is relatively simple, as we do not expect a userId to be supplied it can simply return a static ‘N/A’.

We will follow this by creating another new file src/handlers/optional.js, which will contain the ‘optional’ handler definition.

// @flow

import { createHandler, withOptionalHttpAuthentication } from '../helpers/handlers';

const handler = async ({ userId = 'N/A' }) => ({

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify({ userId }),

});

export default createHandler(withOptionalHttpAuthentication(handler));

In this case we have to cater for the possibility that the userId is optionally supplied to the underlying handler implementation.

Finally, we shall create a new file src/handlers/strict.js, which will contain the ‘strict’ handler definition.

// @flow

import { createHandler, withStrictHttpAuthentication } from '../helpers/handlers';

const handler = async ({ userId }) => ({

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify({ userId }),

});

export default createHandler(withStrictHttpAuthentication(handler));

In this case we can be confident in our assumption that a valid userId will be supplied at all times to the underlying handler implementation.

With the handlers now defined we can update the src/auth.js delivery implementation, which wires the handlers and service dependencies together.

// @flow

import publicHandler from './handlers/public';

import optionalHandler from './handlers/optional';

import strictHandler from './handlers/strict';

import createUserTokenAuthenticator from './services/userTokenAuthenticator';

const { USER_POOL_ID } = process.env;

if (!USER_POOL_ID) {

throw new Error('USER_POOL_ID is not present');

}

const getUserIdFromToken = createUserTokenAuthenticator(USER_POOL_ID);

export const public_ = publicHandler({});

export const optional = optionalHandler({ getUserIdFromToken });

export const strict = strictHandler({ getUserIdFromToken });

We could have just as easily provided these concrete handlers in separate files, but as this is only an example (and two require the getUserIdFromToken service) this will suffice.

If we now run make deploy with this updated implementation, we should see that no externally visible behaviour has changed.

What we have done, however, is clearly separate the domain logic from the delivery mechanism.

This means that we can now easily test the handler domain in isolation, without the need for a concrete Cognito-backed getUserIdFromToken service or API Gateway request.

Testing the Domain Logic

We can now begin providing test coverage to the three handler implementations, to ensure that we are confident in their roles.

To do this we will first extend the global test environment that Jest provides the tests with.

We will do this by adding a small helper function that will be used to parse the response returned from the handlers.

This can be achieved by adding a setupFiles entry to the package.json file.

{

"jest": {

"setupFiles": ["./jestSetup.js"]

}

}

With this now defined, we can add the src/jestSetup.js file as follows.

global.parseResponse = response => {

expect(response).toMatchSnapshot();

response.body = JSON.parse(response.body);

return response;

};

You can see that the helper performs a snapshot assertion based on the response input, before doing any transformations.

Snapshot testing is a very powerful way of ensuring that a desired structure (React component, Object) does not unexpectedly change.

With this helper now available within our test environment, we can move on to testing the public handler use case within src/__tests__/public.js.

import handler from '../handlers/public';

it('successfully responds with no user id', async () => {

const services = {};

const response = parseResponse(await handler(services)({}, {}));

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(200);

expect(response.body.userId).toBe('N/A');

});

it('successfully responds with no user id when access token found', async () => {

const services = { getUserIdFromToken: () => Promise.resolve('USER_ID') };

const response = parseResponse(

await handler(services)({ headers: { Authorization: 'TOKEN' } }, {})

);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(200);

expect(response.body.userId).toBe('N/A');

});

Within each test case we are able to take advantage of async/await syntax to succinctly handle the asynchronous handler response.

Due to how we have delayed the inclusion of any service within the handler, we are able to easily provide any test doubles we see fit.

With the concrete handler now created, we only need to supply the API Gateway Event and Context objects.

If we wished to further distance ourselves from the AWS Lambda specifics, we could provide an interface that each delivery must implement to normalise the handler requirements.

Finally, we inspect the parsed response and assert that it matches our intended state.

If we now run make test, we can see that the first test cases are now successfully executed.

Upon this first execution you will notice that a src/__tests__/__snapshots__ directory is created.

This stores the expected state based on the snapshot assertions we have included in the parseResponse function.

We can now carry on and test the optional handler’s behaviour within src/__tests__/optional.js.

import handler from '../handlers/optional';

it('successfully responds with no user id when access token not found', async () => {

const services = { getUserIdFromToken: () => Promise.resolve() };

const response = parseResponse(

await handler(services)({ headers: { Authorization: 'TOKEN' } }, {})

);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(200);

expect(response.body.userId).toBe('N/A');

});

it('successfully responds with a user id when access token found', async () => {

const services = { getUserIdFromToken: () => Promise.resolve('USER_ID') };

const response = parseResponse(

await handler(services)({ headers: { Authorization: 'TOKEN' } }, {})

);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(200);

expect(response.body.userId).toBe('USER_ID');

});

These test cases follow the similar Arrange, Act, Assert pattern that is found in the previous one.

Finally, we can test the strict handler behaviour within src/__tests__/strict.js.

import handler from '../handlers/strict';

it('fails to respond when access token not found', async () => {

const services = { getUserIdFromToken: () => Promise.resolve() };

const response = parseResponse(

await handler(services)({ headers: { Authorization: 'TOKEN' } }, {})

);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(401);

expect(response.body.title).toBe('Unauthorized');

});

it('successfully responds with a user id when access token found', async () => {

const services = { getUserIdFromToken: () => Promise.resolve('USER_ID') };

const response = parseResponse(

await handler(services)({ headers: { Authorization: 'TOKEN' } }, {})

);

expect(response.statusCode).toBe(200);

expect(response.body.userId).toBe('USER_ID');

});

With all three handlers now covered by tests, we can re-run make test and assert that the code behaves as intended.

Adding Continuous Integration using Travis CI

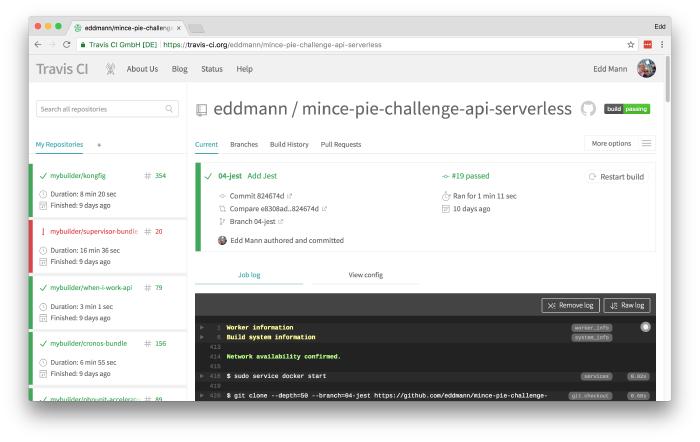

We have now spent some time introducing a type system and test coverage to our project. All would be in vain, however, if they were not run on a regular basis. With this in mind, we will introduce Travis CI into the project, which is a Continuous Integration service that integrates with GitHub.

Our goal will be to re-run both the type checks and test coverage upon each new commit to the remote GitHub repository.

In doing so, the service will alert us to any test regressions along the way.

As Travis CI integrates seamlessly with GitHub, it is very easy to connect and provide a repository configuration by way of a root .travis.yml file.

sudo: required

services:

- docker

env:

DOCKER_COMPOSE_VERSION: 1.21.1

before_install:

- sudo rm /usr/local/bin/docker-compose

- curl -L https://github.com/docker/compose/releases/download/${DOCKER_COMPOSE_VERSION}/docker-compose-`uname -s`-`uname -m` > docker-compose

- chmod +x docker-compose

- sudo mv docker-compose /usr/local/bin

- docker-compose --version

script:

- cp .env.example .env

- docker-compose run --rm serverless npm install

- docker-compose run --rm serverless npm run flow

- docker-compose run --rm serverless npm test

Looking at the configuration above, you will see that we take advantage of Docker, running the container commands as we would in our local environment.

Docker comes as standard within the Travis CI environment, but Docker Compose does not.

As a result, we must first ensure that we have the desired version present for use.

We can then set up a dummy .env file (which is required by our Docker Compose configuration), and then test the build.

If any command returns a non-zero response, Travis CI assumes this to be an issue and will fail the build.

You can see how a successful build looks in the screenshot below.

We now have a well-equipped Continuous Integration pipeline in place. Join me in the next post of the series, where we will begin implementing the Bootstrap API endpoint, experimenting with running the endpoint locally using Serverless Offline.