Rewriting the santa-lang Interpreter in Rust, Part 3 - Performance

Now that we have discussed building the core language and desired runtimes, it is time to highlight one of the biggest reasons why I decided to rewrite the interpreter in a lower-level systems language - performance! In this post, I will document how I went about benchmarking the two implementations (TypeScript/Node and Rust), greatly improving performance and highlighting interesting findings along the way.

All benchmarks require a stable base, and as such, I decided to concentrate my efforts on the CLI runtimes. This runtime is the one I use the most whilst developing Advent of Code solutions over the course of December.

Sizing It Up…

The first point that struck me was how much smaller the Rust binary artifact was - 3.8MB vs 47MB.

This is a bit of an unfair comparison as the TypeScript version is required to package up the entire Node runtime in order to be self-executable.

However, it did show how much smaller the same behaviour could be modelled in.

I was able to reduce the Rust binary size further using several build configuration options: strip, codegen-units, lto.

Initial Benchmarks

Thanks to solving the Advent of Code 2022 calendar in santa-lang, I had a good suite of examples for benchmarking the two variants. Coupled with this, I included some simple examples which documented common language constructs that were present within the language, i.e., arithmetic, recursion, and looping. One such example used recursion to compute the nth term in the Fibonacci sequence:

let fibonacci = |n| if n < 2 { n } else { fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2) };

fibonacci(20);

Another example included a large arithmetic operation to test how the interpreter coped with parsing and evaluating such an expression. I also included an example which was an empty file to baseline the interpreter’s fixed overheads. To provide reliable benchmark results for these examples, I used hyperfine with the following configuration:

hyperfine

-n ts "./santa-cli-ts fibonacci.santa"

-n rs "./santa-cli-rs fibonacci.santa"

--time-unit millisecond

--warmup 3

--export-json fibonacci.json

--runs 10

With this framework in place, I went on to perform my initial round of benchmarks on the two variants and was shocked by the results.

Several Rust example executions resulted in expected significant performance gains compared to the Node variant, thanks in large part to the quicker initialisation times and lighter-weight evaluator Object model.

However, there were many cases where the Node variant outperformed the Rust version - and not by small margins?!

Let’s Get Profiling

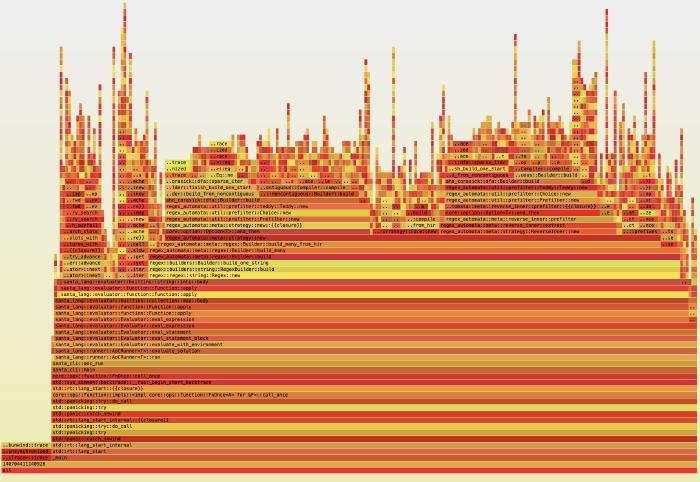

It was at this time that I delved deeper into the Rust implementation, instrumenting my code to profile how much time was spent at each step. I additionally spent some time adding the ability to produce flame graphs, which allow you to clearly visualise the profile output:

Infix Operators

Looking at these initial flame graphs led me to several changes in how infix operators were executed. As the language supports the use of these operators within infix position as well as by function call, I had provided this functionality by way of shared Rust built-in function definitions. This incurred a function invocation per infix operator, so instead, I opted to inline these functions. Paying attention to not being hit by CPU cache performance penalties, I noticed the needless function stack allocations disappear. Although this did help with performance, it still was not the boost that I had been hoping for, so the journey continued…

Environment Variables

The next step I took was to replace the hash map implementation I used within the environment that holds scoped variables. I had noticed that time was spent resolving these environment variables, so I explored replacing the inbuilt hash map with a quicker (although less cryptographically secure) alternative, FxHashMap. This again did not reap the rewards that I had been hoping for, and instead, thanks to a very interesting post, I opted to use a vector to represent the environment variables. This provided quicker variable resolution, whereby it was, interestingly, more performant to traverse a sequential list in memory than apply a hash and resolve the variable from a determined bucket. This performance improvement was based on the code heuristic that there would be a limited number of variables per scope. Sadly, after additional benchmarking, this chipped away some execution time, but I was still not satisfied.

Memory Allocation

I thought I needed to take a different approach and turned my attention to the Node variant. One train of thought I had was that maybe the Node’s performance was better for some use cases due to the included just-in-time compiler (JIT), with ‘hot paths’ being compiled to native code. To check this, I explored disabling the Node JIT and was amazed at how much less performant it was. Perhaps this was as far as I could go with a simple tree-walking interpreter…

All my benchmarks to date had been performed on macOS, and to garner additional insights into my performance woes, I decided to use a Linux tool, perf. What surprised me when I ran the examples on Linux was how much more performant they were - they were blowing the performance of the Node variant out of the water!? After closer inspection, I pinpointed that this was due to the different default memory heap allocators used in the two operating systems. Linux was using jemalloc, touted for reducing memory fragmentation, which is invaluable when performing many small memory heap allocations like santa-lang does. Due to this finding, I changed the default Rust allocator and was able to see a comparable performance increase when executing the solutions on macOS!

I felt like this was a good place to stop tuning the interpreter for performance at this time and enjoy the performance improvements that I had managed to achieve to date.

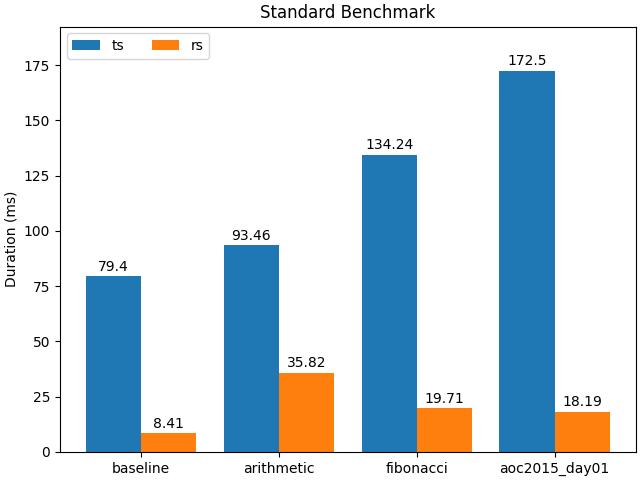

Final Benchmarks

With all the performance tuning out of the way (for the time being), it was time to see how much more performant the Rust variant was compared to its TypeScript compatriot. Below is a graph (created using Matplotlib) benchmarking the example scripts I used to model typical language feature usage:

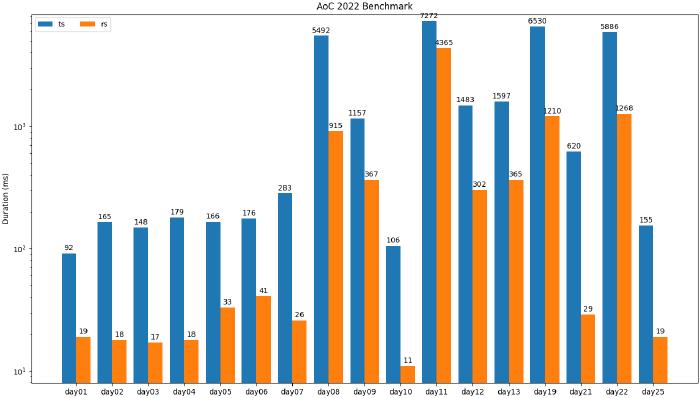

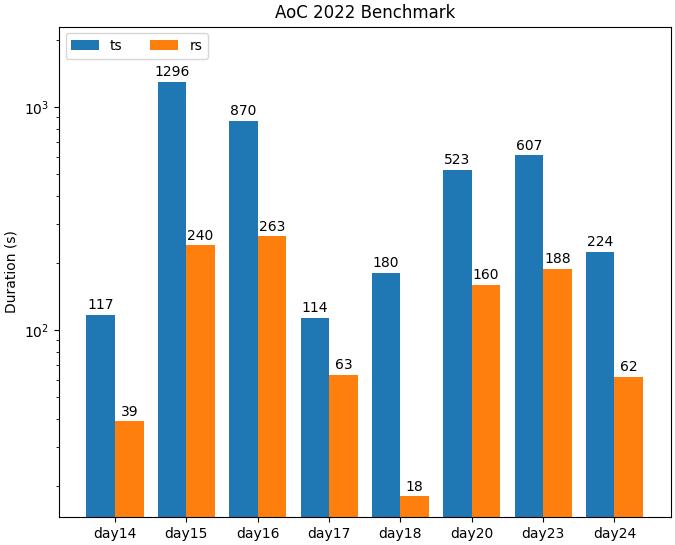

Visualising the benchmarks for the Advent of Code solutions proved to be a bit trickier due to some solutions being orders of magnitude slower than others. As such, I broke these findings into two graphs, the first using milliseconds as the unit of measurement:

And the second graph using seconds as the unit of measurement:

As you can see, in all cases, the Rust interpreter significantly outperforms the TypeScript implementation! As this was the main goal of the project, I was very satisfied with these findings. It had been a journey to get to this point. However, I knew that by delving deeper into the performance realm, there were plenty more improvements to be made. I had only really touched upon the low-hanging fruit - with more drastic changes, such as compiling to closures, the addition of a JIT, and even implementing a full-blown virtual machine being viable options going forward.

What’s Next?

Now that I have been able to explore and document the performance improvements I could make to the Rust implementation, I want to switch tracks and look at one last important topic - distribution. In the last post within the series, I will discuss how I built out a CI/CD pipeline to handle packaging and distributing the different runtimes to their relevant targets. This proved to be an interesting endeavour in itself.